Since Newton was settled in the 17th century, women have played major roles in the community’s survival and success.

Women have helped shape both the city of Newton and the world beyond, in government, the arts, social justice and more. Without women’s contributions to culture and society, Newton and the nation would likely be a lesser place to live.

Women’s rights and some accomplishments people may take for granted today were made possible by women taking bold steps in the past.

Here are eight notable women from Newton’s history.

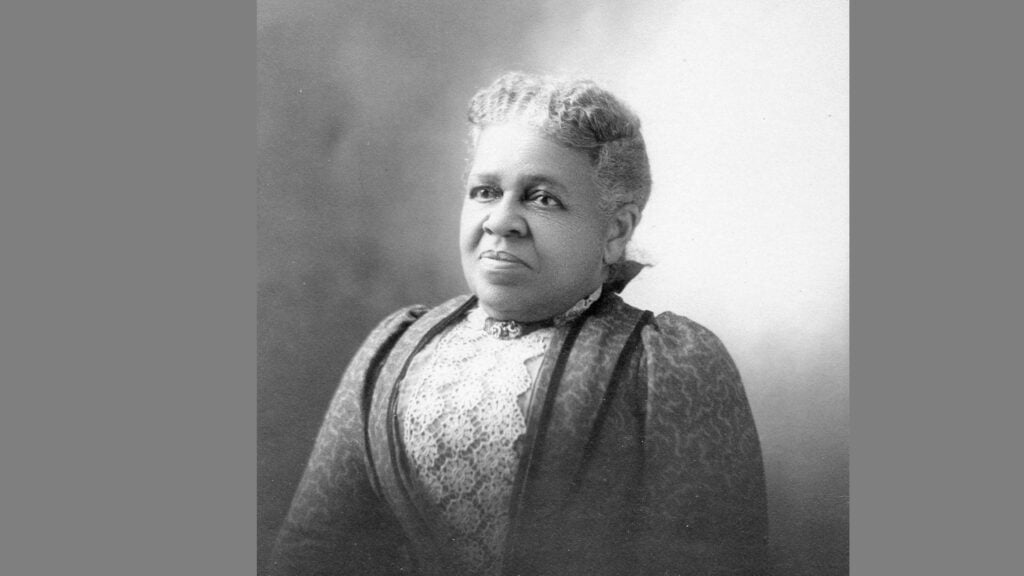

Martha Johnson

When Martha Johnson and her husband, Thomas, moved from North Carolina to the Boston area in the late 1860s, they hoped to find a better life. They may not have expected to help build a thriving Black community west of Boston and a church in the middle of it all.

The Johnsons moved to Newton in part because of the community’s reputation as an abolitionist hub, a stop on the Underground Railroad and home to such abolitionist icons as Nathaniel Allen.

After a few years of attending the Lincoln Park Baptist Church, the Johnsons and other Black residents wanted their own church, one where they could sit in the front pews, sign what they wanted and worship as they pleased.

The Black members of the church voted to separate from Lincoln Park and form their own church, and thus the Myrtle Baptist Church in West Newton was born.

Martha Johnson, along with the other founding women of Myrtle Baptist, helped create a community for Black Americans to set down roots and raise families. They are responsible for much of the diversity we see in the MetroWest region today.

Pamela Sparhawk

Pamela Sparhawk made history in 1818 when she petitioned the government to recognize her for her brother’s estate. The road there was long and painful.

Born in Africa in 1761 Pamela was abducted by slavers as a small child with her brother. The siblings were taken to Jamaica, then to Boston where they were separated, and Pamela was given to a member of the wealthy Boylston family. Pamela was also rented out to merchants for months at a time, providing the Boylston widow with income.

The Boylston widow later moved to Newton to live with her daughter and son-in-law, Rev. Jonas Meriam, and brought Pamela with her to serve in her new home.

Rev. Meriam set her free during the American Revolution, but she stayed with his family to work, given the shortage of opportunities for Black people at the time. Pamela married David Sparhawk, a free Black man, in 1780 and the couple moved to what is now Brighton to start their family.

Her brother, Samuel, had lived as a free man in Boston and owned land in what is now Somerville. When Samuel and his wife died and left no children behind, Pamela was herself a widow and petitioned the Massachusetts General Court in 1818 for recognition as the rightful heir to her brother’s estate.

There’s no record of a response from the state, and since she stayed in her home afterward and not on her brother’s land, it’s believed her request was not granted.

But in asserting her right and her agency at a time when Black people, especially Black women, had so little room to do so, Pamela Sparhawk took one of the first bold steps in Greater Boston’s path toward racial and gender equality.

Margaret Spear

By 1940, there had only been 15 women serving in the history of the Massachusetts legislature.

Margaret Spear of Newton decided to try to become number 16. She succeeded and became the first female state legislator from Newton.

Spear represented the 5th Middlesex District in the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1941 to 1950, during a time of great change and expansion within the state.

Spear jumped into a political arena designed for men, for seat in a state government dominated by men, and in doing so she made big footprints in the pathway for women in politics.

Adelaide B. Ball

Adelaide Buckingham Ball was the first woman to serve on Newton’s Board of Aldermen (the city’s legislative body that later became the City Council).

Born in 1898, she lived in Newton Corner her whole life, the daughter of William Sheldon Ball, an alderman. Adelaide Ball grew up and decided to follow her father’s path and ran for the Board of Aldermen, winning a seat representing Ward 1 in 1953.

Ball would serve in that seat for four years, until she was defeated in 1957. In 1959, she ran for the Ward 1 at-large seat and won, and she served in that seat until 1971, when she retired.

Ball was also passionate about community involvement. She served on the Board of Directors for Newton Junior College and the Newton Mental Health Center. She was a member of both the Newton Republican Club and the Newton Women’s Republican Club. And she was active with the Girl Scouts and the United Fund War Campaign.

Ball died in 1983, leaving a legacy of a city with more opportunities for women in government.

Esther Burgess

There’s everyday bravery, and then there’s Esther Burgess courage.

Esther Burgess, the wife of an Episcopal bishop, lived in Newton Centre and became involved in the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. She was born in Canada but moved to North Carolina for college and met her husband there. The couple eventually settled in Newton in 1958.

In 1964, Burgess joined a group of women—a group that included Mary Peabody, mother of then-Gov. Endicott Peabody—on a trip to St. Augustine, Fla., to help Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference challenge racial segregation there.

The trip gained a lot of attention, and while the initial purpose was to convince local St. Augustine officials to desegregate, Burgess—the only Black woman in her group—decided to join Black protesters and risk being arrested.

The mission first involved sitting down at local restaurants and then leaving once they were refused service, as a way of drawing attention to the cause. But as the group was refused by more and more businesses, they started refusing to leave.

Burgess was arrested on March 31, and she gave a statement to the Boston Globe .(access limited) Looking at the police dog next to her, Burgess joked to the reporter, “I minded my business and he minded his,” before heading into a crowded jail.

Burgess and her husband eventually moved to Connecticut for retirement, leaving a legacy of steadfast courage in the face of injustice that helped a movement change a whole nation.

Nancy Schon

The next time you’re in Boston admiring the “Make Way for Ducklings” statue at the Boston Public Garden, you can thank Newton artist Nancy Schon for the smile.

Schon has lived in Newton since the 1960s and graduated from Boston University and Tufts before attending law school at Mt. Ida College.

She embarked on a life of art, focusing on sculpture and copper sculpture in particular. In 1987, Schon created the famous statue, “Make Way for Ducklings,” inspired by the 1941 children’s book of the same title by Robert McCloskey.

The sculpture quickly gained national fame. And when First Lady Barbara Bush met with Russia’s first lady, Raisa Gorbachev in 1991 in Boston, they met at Schon’s ducklings sculpture. Mrs. Gorbachev reportedly loved the sculpture so much, Mrs. Bush had a duplicate sculpture made and delivered to her Russian counterpart in Moscow as a gesture of friendship.

There has been speculation that the sculpture helped ease diplomatic tensions between the United States and Russia as the Soviet Union saw its dying days. For that small part in softening the Cold War, Schon has shown that art can bring people, and perhaps cultures, together.

Audrey Cooper

Late next year, there will be a new senior community center in Newtonville—a large, multi-story activity center for seniors and the city’s residents at-large—aimed at keeping people active and engaged as they age.

And it’s named after Audrey Cooper, one of the most active and engaged residents in Newton’s history.

Audrey Cooper, a longtime West Newton resident and city icon, chaired the Board of Trustees of the Newton Free Library and co-chaired the committee to establish the Newton Senior Center. She helped Family Access of Newton set up early childcare and after-school programs and worked for the city’s public schools for decades.

The Newton Human Rights Commission awarded her the Newton Human Rights Award, and the Massachusetts Commission on the Status of Women named her one of their Unsung Heroines.

Audrey Cooper passed away in 2021 at the age of 97, and she leaves a legacy of service that could fill a hundred lifetimes.

Ruthanne Fuller

There was a time when the people on Newton’s list of mayors—all 32 of them—were men. That changed in 2017, when Newton elected its first woman mayor, Ruthanne Fuller.

Fuller represented Ward 7 as an at-large alderman, and then city councilor, for seven years, focusing the city’s attention on fixing and replacing old school buildings and stormwater systems and pushing for more long-term financial planning.

Before getting into government, Fuller, a graduate of Brown University and Harvard Business School, worked as a strategic planner for businesses and nonprofit organizations.

As mayor, Fuller has had reasons to celebrate. The city has maintained a AAA bond rating while pushing ahead with an ambitious public buildings reconstruction renaissance that rivals post-World War II. And Newton just reached its affordable housing “safe Harbor” status for the first time. But last year, voters rejected Fuller’s Proposition 2 1/2 override request for $9.2 million, and the schools, with needs that have risen sharply while school budgets have not. Fiscal stress over the past several years triggered a two-week teacher strike this winter.

In a city of almost 90,000 people, smooth sailing can be a rarity, but there’s added honor being the first woman to command the ship.

The post Eight notable women in Newton’s history appeared first on Newton Beacon.

0 Comments